- Research

- Published:

Social isolation and loneliness among people living with experience of homelessness: a scoping review

�������� Public Health volume��24, Article��number:��2515 (2024)

Abstract

Social isolation and loneliness (SIL) are public health challenges that disproportionally affect individuals who experience structural and socio-economic exclusion. The social and health outcomes of SIL for people with experiences of being unhoused have largely remained unexplored. Yet, there is limited synthesis of literature focused on SIL to appropriately inform policy and targeted social interventions for people with homelessness experience. The aim of this scoping review is to synthesize evidence on SIL among people with lived experience of homelessness and explore how it negatively impacts their wellbeing. We carried out a comprehensive literature search from Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, and Web of Science's Social Sciences Citation Index and Science Citation Index for peer-reviewed studies published between January 1st, 2000 to January 3rd, 2023. Studies went through title, abstract and full-text screening conducted independently by at least two reviewers. Included studies were then analyzed and synthesized to identify the conceptualizations of SIL, measurement tools and approaches, prevalence characterization, and relationship with social and health outcomes. The literature search yielded 5,294 papers after removing duplicate records. Following screening, we retained 27 qualitative studies, 23 quantitative studies and two mixed method studies. SIL was not the primary objective of most of the included articles. The prevalence of SIL among people with homelessness experience varied from 25 to 90% across studies. A range of measurement tools were used to measure SIL making it difficult to compare results across studies. Though the studies reported associations between SIL, health, wellbeing, and substance use, we found substantial gaps in the literature. Most of the quantitative studies were cross-sectional, and only one study used health administrative data to ascertain health outcomes. More studies are needed to better understand SIL among this population and to build evidence for actionable strategies and policies to address its social and health impacts.

Introduction

Social isolation and loneliness (SIL) are major social and health issues representing a growing global public health challenge, particularly for socio-economically excluded and underserved populations [1, 2]. Social isolation is defined as a lack of close or meaningful relationships and results from multidimensional experiences associated with exclusion from mainstream society, hopelessness, abandonment, social marginalization, lack of community networks and dissatisfaction with relationships [3, 4]. Loneliness is a more personal and subjective multifaceted experience consisting of different types of self-perceived social deficits, including social loneliness, defined as a self-perceived lack of friendships in either quality or quantity and emotional loneliness, experienced as a deficit of intimate attachments such as familial or romantic relationships or feeling alone and isolated [3,4,5].

SIL has been linked to putting people at increased risk for adverse health outcomes, social distress and premature death [6]. Lack of adequate social support has been reported to increase the odds of premature death by 50% [6]. Previous studies have also found an association between SIL and increased risk of developing dementia, coronary heart disease and stroke, poorer mental and cognitive health outcomes, and consumption of a low-quality diet [7, 8]. While SIL affects many populations, individuals with experiences of being unhoused are among those with the highest risk of being socially isolated and lonely. First, experiences of homelessness are visible and extreme forms of social exclusion. Unhoused people are more socially disconnected, can feel rejected or abandoned, and may not have appropriate informal (family, relatives, friends) and formal support networks [9, 10]. Second, even after being housed, structural forms of oppression (i.e., racism) and discrimination associated with previous experiences of being unhoused continue to impact individuals’ lives and deprive people of meaningful recovery and social integration, connection and relationships [11,12,13]. Individuals who have experienced homelessness often face persistent stigma and discrimination that can affect their social interactions and access to essential services [12]. People with experiences of being unhoused have self-reported higher odds of poor mental and physical health and loneliness than their housed counterparts [14]. Moreover, people with experiences of being unhoused have lower life expectancy and experience impairments associated with aging earlier compared with people without experiences of being unhoused [15,16,17]. These factors can make individuals more vulnerable to social and economic abuse, which may affect their ability to build meaningful social connections.

Recent years have seen increased initiatives to address SIL among formerly homeless populations. There is some consensus in social work to consider SIL in needs assessments for health and social care for some specific population groups, such as seniors and youth [18, 19]. More resources are being allocated to address SIL in supportive housing programs and intervention design [20]. Social prescribing, which involves primary care physicians prescribing social activities to patients as a strategy to strengthen social engagement and lower loneliness, is becoming a growing practice [21, 22]. Nonetheless, SIL remains complex to conceptualize, and it has been difficult to measure its prevalence and association with social and health outcomes and other indicators of wellbeing. Without a clear conceptualization and measurement approach, it is uncertain how to design adequate interventions and policies to address SIL.

The aim of this scoping review was to identify, map, and synthesize the findings of qualitative and quantitative studies that measure SIL among people over the age of 18 with lived or living experience of homelessness including those living in supportive or social housing, or staying in emergency or transitional accommodation in order to highlight the gaps in the existing literature and inform the development of future interventions. This scoping review will aim to answer the following questions:

-

How are SIL conceptualized across studies involving people with experience of homelessness?

-

What scales and tools are used to measure SIL across these studies?

-

What is the prevalence of SIL and the relationship between SIL and social and health outcomes in people with experience of homelessness?

Methods

Data sources and searches

The scoping review protocol followed the methodology outlined by Arksey and O’Malley, Levac et al. [18] and is guided by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA ScR) [23]. Initially, a preliminary search was performed in Medline and Embase to identify any existing scoping reviews related to the topic, and to refine the search strategies by pinpointing key concepts and determining an appropriate timeframe to include relevant studies [24]. Then, comprehensive literature searches were carried out by an information specialist (CZ) in Medline (Ovid platform), Embase (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials & Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), and Web of Science's Social Sciences Citation Index and Science Citation Index. The search strategies had a broad range of subject headings and keywords, adapted for each database, for the two core concepts of SIL and homelessness or social housing, combined with the Boolean operator AND. The searches were limited to articles in English, French, and Spanish published between January 1st, 2000 to October 27, 2021, followed by an updated search to January 3rd, 2023. The publication languages were chosen for feasibility purpose, considering the linguistic capacity of the research team. Comments, editorials, and letters were excluded from the search. There were a total of 8,398 results from these two rounds of searches prior to de-duplication (7,356 at search one and 1,042 at search two) and the records were compiled in EndNote. The complete search strategies as run are included in the Supplementary material.

Definition and screening process

To refine our screening process, we defined individuals experiencing homelessness as those lacking stable, safe, permanent, and appropriate housing, or the immediate means and ability to acquire such housing [25]. This definition encompasses individuals who are marginally housed or at high risk of eviction, including individuals who are "doubled up," couch surfing, or living in overcrowded conditions [26].

To be considered eligible for inclusion, we established the following inclusion criteria for the scoping review:

-

studies had to include participants that were people with homelessness experience or marginally/vulnerably housed populations (people living in supportive housing or shelters). While our screening process did not establish an age criterion, we excluded studies that focused exclusively on minors (under 18��years old) experiencing homelessness. This decision was made as a recent study showed that minors experiencing homelessness might need specific considerations and theoretical framework [27];

-

studies had to be peer-reviewed qualitative and quantitative original research papers published in English, French, or Spanish;

-

studies had to be published between 2000-and January 3, 2023;

-

studies had to examine or include in the analyses: loneliness, social isolation, social disconnection, solitude, social withdrawal, abandonment, lack of contact, social exclusion or rejection.

We excluded papers that were systematic or scoping reviews, and��papers where the studied populations was exclusively minors; where the field activities and data were collected from caregivers or other workers, and not people with homelessness experience or marginally/vulnerably housed; studies that only focused on networking, social or community integration and did not refer to social isolation or loneliness. No exclusion was made based on geographic region or countries, however we excluded studies that focused on people residing in camps due to displacement from war, insecurity, or major natural disasters, as these situations are typically addressed by different theoretical and humanitarian frameworks [28].

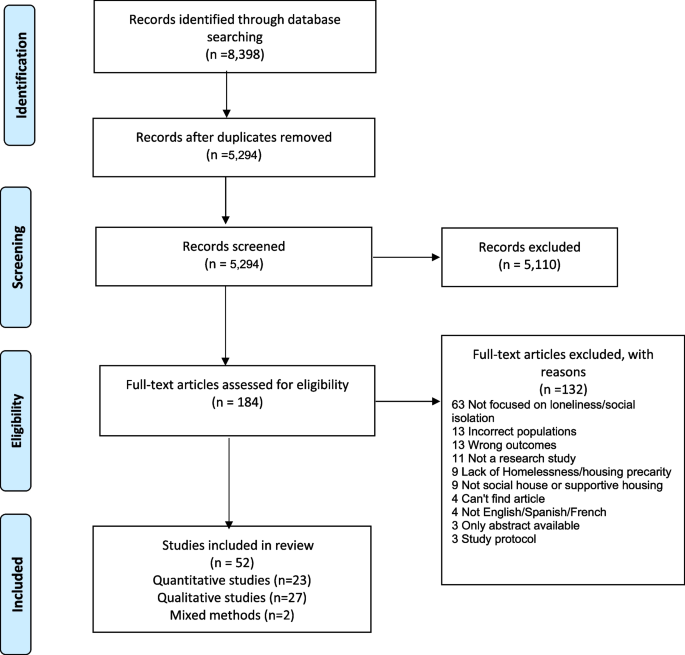

The results from all searches were imported to Covidence systematic review software, where duplicates were removed. The searches yielded 5,294 papers for screening after the deletion of duplicates. Four researchers (AY, EG, FM, and MP) screened the article titles and abstracts independently and in duplicate in Covidence using the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full-text of the articles that met our eligibility criteria were then assessed by two independent reviewers. At both stages, differences in voting were discussed and resolved as a group, and included the Principal Investigator (JL). In total, 52 articles met the criteria for data extraction and analyses. The PRISMA diagram in Fig.��1 shows the flow of information through the different stages of the review.

Data extraction

The main characteristics, research questions, targeted populations, measurement and findings of the selected studies were extracted in an Excel database file by the four researchers (AY, EG, FM, and MP) and reviewed by the Principal Investigator (JL). A summary of each selected paper can be found in Tables 1 and Table��2.

Data synthesis

The studies reviewed exhibited considerable variability in their methodological approaches, participant demographics (including young adults, adults, and seniors) or sex and gender-based groups, measures of SIL, definitions of homelessness experience, and countries where they were conducted. To provide a thorough overview, we examined both quantitative and qualitative research. Initially, we assessed the theoretical frameworks used in these studies to better grasp the conceptualization and ongoing discussions about SIL within the target population. In our analysis of quantitative studies, we identified key similarities and differences in SIL measurements, demographic characteristics, discussions of the prevalence and patterns of SIL and its relationship with health status. To deepen our understanding, we used a crosswalk approach [29] using both quantitative and qualitative studies to examine how participants described, contextualized, and nuanced their experiences of SIL, and how SIL related to demographic factors, gender, and homelessness experience.

Results

Overview of included studies

The main characteristics of the 52 articles included in this review are outlined in Tables 1 and Table��2. Most articles (n = 42) were published from 2010 and later and were conducted in the US (n = 16) and Canada (n = 16). Study methodology was almost evenly split between quantitative (n = 23) and qualitative (n = 27) methods, and a very small number (n = 2) used a mixed methods approach. Among quantitative studies, 18 had a cross-sectional or one-point-in-time design, and 5 used a longitudinal design. Most of the qualitative studies (15) used a thematic analysis approach.

Characteristics of the populations covered in included studies

Among included articles, 4 focused on women [30,31,32,33] and older women [34]; 5 studies examined male [35,36,37,38] or older male populations [39]. In total, 10 articles focused on older adults, which usually included early aging starting from 50 years [40] or 55��years [41] of age and above for populations with experience of homelessness. We found no studies that focused on non-binary groups, though gender-diverse self-identified individuals were included in 6 of the studies [33, 42,43,44,45,46]. Moreover, there were a small number of studies (n = 6) focused on youth. Three of these were quantitative studies [47,48,49] comparing homeless youth and young adults to youth in the general population. The other 3 were qualitative studies [50,51,52]; 2 described how youth experience loneliness [51, 52]; one study identified strategies for dealing with feelings of loneliness among homeless adolescents [50]. Three studies [53,54,55] focused on a population of veterans who were currently experiencing homelessness or were formerly homeless and living in either subsidized or supportive housing. Participants’ ethnicity was reported in most of the studies (n = 32).

Social isolation and loneliness as the primary objective

Only 18 of the 52 studies focused on SIL as their primary objective or included SIL in the main research questions. Of these 18 studies, 13 were quantitative and 5 were qualitative as summarized in Tables 1 and��2. In the remaining 34 articles, SIL neither was the main objective nor clearly stated in the objectives or research questions. In those studies, SIL was usually considered as one of the potential explicative or control factors [30, 56, 57], and eventually emerged or co-created from participants’ narratives.

Conceptualization of social isolation and loneliness

Different theoretical frameworks were used to contextualize SIL in relation to unhoused or homelessness experiences. For some studies, SIL was embedded in the homelessness experience, since homelessness is in itself a form of social exclusion, which limits people’s participation in society [36, 58]. Lafuente et al. [36] explained the experience of unhoused men through the lens of social disaffiliation theory. They explained that situational changes (i.e., loss of employment) or intrinsic factors (voluntary withdrawal) caused participants to become socially disaffiliated. Narratives on isolation from this study revealed feelings of alienation, powerlessness, self-rejection, depression, loneliness and unworthiness. Similarly, the study by Burns et al. [39] explained how the transient nature of being unhoused creates interrelated dimensions of social exclusion, generating a sense of invisibility, identity exclusion, racism, exclusion of social ties and meaningful interactions with the community, thus leading to social isolation.

Bell and Walsh [37] conceptualized SIL among individuals experiencing homelessness as being driven by mainstream normative conceptions of homelessness and the stigma of homelessness. The authors suggest that conceptions of homelessness conflate between notions of “rooflessness” and “rootlessness” which “denotes the absence of support and inclusion in one’s community driving experiences of isolation and loneliness.” [37].

In the study by Baker et al., [58] SIL is discussed as part of a new landscape of a network society and digital exclusion. The rapid development of information and communication technologies (ICT) has drastically changed human communication and interactions leaving many behind and out of communication flows. The authors explained that aging combined with many social disadvantages like histories of homelessness, multiple complex needs, rural areas of residence, and economically restricted mobility can contribute to creating or keeping affected older adults disconnected and socially isolated.

Meaning and experiences of social exclusion and, in particular SIL were further voiced through semi-structured qualitative interviews or focus groups in different studies. Often, participants reflected on how broader structural stigmatization and alienation associated with housing insecurity contributed to their perceived SIL. Jurewicz et al. [59] highlighted how systemic policies and practices affecting individuals experiencing homelessness who used substances generate and contribute to ongoing experiences of housing precarity, loneliness and isolation. Participants further discussed the complex interrelationship between substance use and homelessness including the strain on social relationships as a result of substance use [59]. Similarly, Martínez et al., [60] described how experiences of loneliness are driven by a lack of meaningful relationships, conflicts with families, a lack of social inclusion, and marginalization faced by individuals residing in a residential center in Gipuzkoa, Spain. In the study by Johnstone et al., [61] social isolation was defined as being associated with not having perceived opportunities to develop multiple group memberships.

Experiences and conceptualizations of loneliness were not strictly dependent upon one’s lack of access to housing. Two studies discussed how the transition into supportive or transitional housing further exacerbated experiences of loneliness and isolation [53, 62]. Polvere, Macnaughton and Piat [62] and Winer et al. [53] highlighted that the transition to living within congregate-supported settings or independent apartments can be linked to experiences of SIL even when people are offered social engagement activities. Some participants reported feeling voluntarily isolated as they did not want to engage with others and some participants anticipated social isolation due to transitioning into a new environment.

Measurement tools to assess social isolation and loneliness

There were multiple approaches to measuring SIL across all studies, including widely used and validated multi-item scales and single-item measures. There were three main scales that were��developed, revised, tested or used to measure SIL among people experiencing homelessness: The Rokach Loneliness questionnaire, the UCLA Loneliness Scale and its revised versions, and the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale.��

The rokach loneliness questionnaire

Five studies used the Rokach Loneliness Questionnaire [47,48,49, 63, 64]. The Rokach Loneliness Questionnaire [47, 48] measures causes of loneliness and coping strategies and has been used in studies with young people aged 15–30 in Toronto, Canada. The questionnaire measures the experience of loneliness across five factors, with yes/no items on five subscales: emotional distress such as pain or feelings of hopelessness; social inadequacy and alienation including a sense of detachment; growth and discovery such as feelings of inner strength and self-reliance; interpersonal isolation including alienation or rejection; and self-alienation such as feelings of numbness or denial. The items on the interpersonal isolation subscale relate to an overall lack of close or romantic relationships.

The UCLA loneliness scale

Six of the studies in this review used the UCLA Loneliness Scale or a revised version. Novacek et al. [54] assessed subjective feelings of SIL among Black and White identifying veterans with psychosis and recent homelessness compared with a control group at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The 20-item scale was used to measure subjective feelings of SIL over the past month. Participants rated their experience ranging from “never” to “often,” with higher scores indicating higher subjective feelings of loneliness. Lehmann et al. [38] used a revised version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale to examine individual factors including loneliness relevant in people experiencing homelessness to report their victimization to police. The researcher recruited 60 self-identified adult males aged 19 to 67 currently experiencing homelessness in Germany and used a revised and shorter German UCLA Loneliness Scale developed by Bilsky and Hosser [65], to measure loneliness. The scale is composed of 12 items with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 5 (“very much”) and positively formulated items were recorded to reflect a higher level of loneliness. The load factors for the scale are experiences of general loneliness, emotional loneliness, and inner distance. Drum and Medvene [66] used the UCLA-R Loneliness Scale, which has been adapted for an older adult population to measure loneliness among older adults living in affordable seniors housing in Wichita, Kansas. This version is composed of 23 items, with a four-point Likert scale-type of response options. Participants’ total score ranged from 20 to 80, with a higher score representing greater loneliness.

Tsai et al. [67], Dost et al. [68] and Ferrari et al. [69] used a shortened revised version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3, which consists of three items: “how often they feel they lack companionship, how often they feel left out, and how often they feel isolated from others.” Participants self-reported their responses using a 3-point Likert scale (“hardly ever,” “some of the time,” and “often”) to answer questions. A summed score of 3 to 5 is defined as not lonely and a summed score of 6 or more is defined as lonely. The 3-item scale is used widely in research and clinical settings as a short assessment of loneliness.

De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale

Valerio-Urena, Herrara-Murillo and Rodriguez-Martinez [70] examined the association between perceived loneliness and internet use among 129 currently homeless single adults aged 35–60 staying in a public shelter in Monterrey, Mexico. The authors used questions from the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, which includes 11 items with three response options (1 = no, 2 = more or less, 3 = yes) asking about having friends or people to talk with or contact, feeling empty or missing other people’s company, and having people or friends you can trust. The subscales measure emotional loneliness (due to the lack of a close relationship) and social loneliness (due to the lack of a general social network) with scores ranging between 0 (no solitude) and 11 (extreme solitude).

Other social isolation and loneliness scales

Some of the quantitative studies used subscales or single questions from measurement tools that were not primarily designed to measure SIL. For example, Cruwys et al. [71] used the short form of the Young Schema Questionnaire, which included 75 items with five items assessing each of the 15 schemas. This study focused on the social isolation schema, which was described as a “feeling that one is isolated from the rest of the world, different from others, and or/ not part of a group.” Statements included “I don’t fit in; I don’t belong; I’m a loner; I feel outside the groups.” Respondents answered on a 6-point scale from 1 if “completely untrue to me” to 6 if “describes me perfectly.” In this study, participants who responded with 5 or 6 (“Mostly true of me” or “describes me perfectly”) on the scale were assigned 1 point, otherwise they were assigned 0 points.

Wrucke et al. [72] investigated factors associated with cigarette use among people with experiences of homelessness. Social isolation was one of the variables hypothesized to be associated with smoking among this population. The authors used the short form of the social isolation questionnaire developed using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). PROMIS defines social isolation as the “perceptions of being avoided, excluded, detached, and disconnected from, or unknown by others.” It uses a 4-item social isolation questionnaire to capture each of these dimensions, for which the option of responses range from never to always.

In their study, Drum and Medvene [66] used the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS) to measure social isolation in addition to the UCLA-R Loneliness Scale mentioned above. LSNS was used as a measure of risk of isolation and included 10 items; three (3) items referred to family networks, three items (3) to friend networks, and four items (4) to confident relationships. Each of the items had a five-point Likert scale-type response, with the total adding up to a score between 0 and 50. A higher score on the LSNS represents greater risk of social isolation. Participants were categorized based on their LSNS score as low risk (0–20), moderate risk (21–25), high risk (26–30), or isolated (31–50).

Ferreiro et al. [73] used one question from the 22-item Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) to measure loneliness among Housing First program participants in Spain. One item asks, “Does the person need help with social contact?” and the answer is classified as a serious problem if a respondent answered, “Frequently feels lonely and isolated.” Rodriguez-Moreno [31] used the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) which includes a subscale of somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction and depression to study the mental health risk of women with homelessness experience. The GHQ has one question related to “feeling lonely or abandoned.” Similarly, Vazquez et al. [30] reported one question on the extent participants feel lonely or abandoned using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “a lot.” Pedersen, Gronbaek and Curtis [74], Bige et al. [56] and Muir et al. [57] also measured loneliness using one question. Another study by Rivera-Rivera et al. [55] examined factors associated with readmission to a housing program for veterans with a number of measurement tools and administrative data to create a profile of participants. In their study, social isolation was measured using the relationships section of the significant psychosocial problem areas of the Social Work Behavioral Health Psychosocial Assessment Tool where isolation/withdrawal can be measured using “yes” or “no” responses [55]. Finally, Bower [75] piloted the short version of the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA-S) with a group of 129 Australian adults with homelessness experience. However, this paper was excluded from our review as the authors concluded that the SELSA-S seems to be inappropriate to measure loneliness among people with homelessness experience.

Prevalence and scores of social isolation and loneliness: quantitative evidence

The prevalence of SIL varied from 25% to more than 90% across studies included in this review. Based on LSNS risk categorizations, Drum and Medvene [66] found over one-quarter (25.8%) of participants were categorized as being socially isolated and nearly one in five (19.4%) as being at high risk for social isolation. Cruwys et al. [71], using the Young Schema Questionnaire-2 found more than one-quarter (28%) of participants reported elevated social isolation at time T1 (day 1) of the study, with no change in social isolation reported at time T2 (2��weeks after leaving temporary accommodations). An examination by Rivera et al. [55] of 620 patient records of veterans who requested services at the ��������less Program of the VA Caribbean Healthcare System from 2005 to 2014 found that over one-third (34.7%) reported experiencing social isolation. In a study with 1,306 socially marginalized people recruited at shelters and drop-in centres in Denmark, more than one-quarter (28.4%) reported often unwillingly being alone [74]. Bige et al. [56] found that more than 90% of 421 people experiencing homelessness were socially isolated.

Using the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, Herrara-Murillo and Rodriguez-Martinez [70] estimated an average score of 7.12 for loneliness among surveyed participants, which is between moderate and severe loneliness (score = 8). Ferrari et al. [69] also found a high mean score among homeless adults (score = 6) at baseline, based on the revised 3-item UCLA scale. Rokach [64] reported homeless adults had significantly higher mean subscale scores than non-homeless adults on four of five subscales measuring loneliness: interpersonal isolation (3.44 vs 2.82), self-alienation (1.92 vs 1.27), emotional distress (2.97 vs 2.73), and social inadequacy and alienation (2.92 vs 2.70).

Social isolation and loneliness evidence in qualitative studies

Twenty-nine studies reported qualitative evidence with the majority (n = 15) using thematic analysis to convey experiences of SIL among participants with histories of being unhoused or experiences of housing precarity. In most qualitative studies, participants referred to a lack of social connectedness, weak relationships with community members, family, or friends, feelings of abandonment, or a desire to withdraw. In a study by Bower, Conroy and Perz [10], researchers explored experiences of social connectedness, isolation and loneliness among 16 homeless or previously homeless adults ages 22–70 in Sydney, Australia. Participants described feelings of rejection through marginalization and stigma, rejection from family, lack of companionship, and shallow and precarious relationships with others, which made them feel alone [10].

Similarly Burns et al., [39] reported social isolation among older adults with histories of chronic homelessness living at a single-site permanent supportive housing program in Montreal, Canada. Participants revealed that they were socially excluded based on their ethnicity and sexual orientation, which made them feel isolated. Participants in the study by Lafuente [36] attributed their feelings of isolation to experiences of being unhoused and narratives from 10 male-identifying participants centered on discussions of isolation, including feelings of alienation, depression, loneliness, resignation, unworthiness and withdrawal. Participants shared their feelings of being “frightened, sad, lonely, and frustrated” and wanting to “withdraw from society” [36]. Studies by Kaplan et al. [76] and Grenier et al. [41] also reported concerns of social isolation due to lack of strong familial ties among participants, which impacted their engagement with services and contributed to feeling isolated and ostracized.

In a study of 46 adults using shelters and drop-in centres in Denmark, participants reported challenges with developing lasting and meaningful social relationships with others [77]. With data from the 30 participants included in the analysis, the authors categorized SIL into 5 groups: socially related and content (n = 9) characterized by satisfying relations with social and professional groups; satisfied loners (n = 5) centered on social isolation bringing rewards of peace and quiet; socially related but lonely (n = 4) focused on superficial social relations; socially isolated (n = 9) comprised of sporadic social connections; and in-between (n = 3) characterized by broad networks, however feeling unsatisfied with social networks [77].

Other studies focused on experiences of SIL in relation to the negative consequences of being unhoused and experiencing associated stigma. Bell et al. [24] revealed participants’ feelings of worthlessness as a result of the social stigma of being unhoused. Participants described homelessness as: “walking around with a big sign on your head that says, “I’m worthless” … the way you are looked on by society, like you feel like an alien…you always have to leave because you’re not welcome, you’re not welcome, you’re not welcome anywhere. In a town of a million people you are made to feel like you’re by yourself and you’re alone because there is nowhere to go.”��Another study aimed to understand the experiences of SIL among 11 adults ages 22–60 (5 self-identified females; 6 self-identified males) staying in residential centers in Spain [60]. Participants reported feelings of loneliness as a chronic and persistent experience. One participant described it as follows: “I’ve always felt lonely, everywhere I’ve been, even having people around me…It’s not about being physically alone…it’s a loneliness inside.” [60].

Nonetheless, transitioning from homelessness to housing does not imply a reduction in SIL, at least in the short term. Several qualitative studies [53, 62, 78,79,80] were conducted with participants of the At �������� / Chez Soi study, a pragmatic randomized controlled trial in Canada that used a Housing First approach to provide housing and supports to individuals experiencing homelessness and mental health problems [11]. Some participants who received housing experienced loneliness [80] whereas others expressed concerns about not being able to cope with social isolation following a transition to independent housing [62]. Moving into housing can contribute to SIL with a shift from being surrounded by people in congregate settings such as shelters or jail, to living alone [78, 33]. One participant said: “It’s [the transition] hard because I’m used to having people around me all the time.” [62] In a study by Winer et al. [53], some participants who received housing chose not to socialize or build relationships: “But I don’t socialize here at all. I didn’t think, I didn’t realize that I would be so isolated. You know, I could go knocking on doors and try to be friends with people. But I just don’t bother to do that. I’m not interested in reaching out.”

Other studies examining individuals accessing transitional accommodation reported that participants’ positive comments illustrated connections with peers and program staff and these connections resulted in them no longer feeling lonely or isolated [61]. Over one-third (34%) of participants reported positive experiences with respect to their accommodations, interactions with caseworkers and with their peers/other residents, which made them not feel lonely or isolated. Another study [81] found access to supportive housing was also associated with a reduction in drug use; while some participants were spending time alone, they did not report feeling lonely. Some reported having pets and others did volunteer work to help them overcome feelings of social isolation.

Other studies reported SIL among young populations with homelessness experience. A study by Rew [50] conducted interviews and focus groups with 32 homeless youth ages 16–23 participating in a community outreach project in central Texas. Participants discussed reasons for loneliness including personal loss, traveling and being away from family and friends, and at certain times, for example at night, during winter, or specific occasions such as holidays and birthdays: “I just get lonely at night…more at night.” [50] Another study by Johari et al [52] conducted interviews and focus groups with 13 individuals ages 18–29 in Iran about their experiences of homelessness. Participants described feeling lonely, harassed and abandoned by society. Themes that emerged from the interviews included “avoidance of/ by society, comprehensive harassment, and lack of comprehensive support.” [52] Participants reported feeling isolated due to a loss of self-confidence and social trust. One participant shared, “I have nothing to do with anyone, and I am alone.”

Some qualitative studies reported on SIL among people with experiences of homelessness in the context of COVID-19 [51, 79, 82, 83]. These studies explained how social distancing and other public health restrictions disrupted social relationships with housing staff, other residents, family members and communities and reduced access to services. Participants discussed how an increased fear and a lack of social networks exacerbated feelings of social isolation during lockdown periods: “Aside from not being allowed to go out the f… door aye. I’m not allowed out. Everybody else can go for a walk, I am imprisoned in the square.” [83] Another study by Noble et al. [51] analyzed the impact of COVID-19 on 45 youth ages 16–24 living in emergency shelters in Toronto, Canada. Youth stressed that the pandemic and associated public health restrictions (e.g., closed common spaces, canceled in-person activities, social distancing and single-occupancy sleeping arrangements) led to reduced access to important social networks, and an associated increase in feelings of SIL: “Like, right now, because of everyone’s at home, because of the lockdown and you can’t really like meet people […] it’s a very challenging moment, it’s testing me, another limit of me.” [51].

Intersectionality in homelessness, social isolation and loneliness

Using an intersectionality framework, defined as an approach that explores how various forms of discrimination and privilege overlap and interact to influence an individual’s experiences and challenges [84],we analyzed how studies explored the critical role of multiple identities in shaping SIL experiences among people with homelessness experience. People reported different SIL experiences and faced different SIL-related challenges based on their gender [69], ethnicity and sexual orientation [39], and age [48]. For example, Ferrari et al. [69], using the revised 3-item UCLA scale, found women had statistically significant and higher mean loneliness scores (6.29) compared with men (5.57). Using the same scale, Dost et al. [68] reported an average loneliness score of 5.2 (SD = 1.9); among self-identified men it was 5.1 (SD = 1.9) and among self-identified women, it was 5.4 (SD = 2.0) (n = 265 reported frequency of loneliness). Using the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, Herrara-Murillo and Rodriguez-Martinez [70] found younger participants ( < 35��years of age) reported slightly higher levels of loneliness (mean score = 7.88) compared with older adult participants (between 35–60��years of age) (mean score = 7.4). Rokach [47, 48] found homeless youth, compared to young adults, had higher mean subscale scores on interpersonal isolation (3.43 vs. 2.84) and self-alienation (1.91 vs. 1.48).

Other studies among younger populations also described how young people with experiences of being unhoused and coping with SIL are significantly different than their housed counterparts and older adults. Histories of addiction, rejection, trauma, and violence were intertwined with loneliness for young people with experience of homelessness [48, 50,51,52]. A study by Rokach [48] focusing on the experiences of loneliness among homeless youth in a Canadian urban city found that causes of loneliness included feelings of personal inadequacy, developmental deficits, unfulfilling intimate relationships, relocation, and social marginality, which are unique to these groups of individuals when compared with older adults.

Toolis et al. [33] examined how multi-faceted forms of structural inequities faced by self-identified women experiencing homelessness (i.e., stigmatization, violence, and child apprehension) drive social exclusion experiences from services, peers, and broader society. This study illustrated how organizational settings with a culture of acceptance, support and mutuality can help women develop positive affirming relationships with one another that can alleviate feelings of social isolation. In this analysis, participants highlighted how their transgender identity contributed to experiences of isolation and loneliness and how their experiences were driven by forms of oppression prevalent across social service spaces such as co-ed shelters [33].

Association between SIL and health status or outcomes

Among the quantitative studies, only 8 reported direct associations between SIL and health status or outcomes (See Table��3). All of these studies utilized cross-sectional analyses and only one [56] used health administrative data to ascertain health outcomes. The health status and outcomes examined in these studies varied and included self-rated health [74], subjective health status [66], current cigarette use [72], ICU and hospital mortality [56], physical health burden [40], and risk of mental ill-health [31]. Additionally, some studies also examined social distress indicators such as sleep patterns [85], and experiences with eviction [67] or readmission to housing programs [55].

SIL was significantly associated with physical and mental health outcomes for people with experiences of homelessness. Drum and Medvene [66] found a negative correlation between subjective health and SIL (r = -0.39, p > 0.03). SIL was associated with higher odds of reporting poor health and mental health among men (OR: 1.98, 95% CI 1.36–2.88), but not statistically significant for women (OR: 1.71, 95% CI 0.96–3.05) [74]. Another study found participants who reported being sick had a higher level of SIL than those who reported being healthy��(OR: Sick 1.228(0.524) p < 0.05) [70].

Moreover, a study by Patanwala et al. [40] reported that participants in the moderate-high physical symptom burden category had a significantly higher SIL score than participants in the minimal-low physical symptom burden category (AOR 2.32, 95% CI 1.26–4.28)). In addition, homeless veteran participants who reported SIL were 1.36��more likely (95% CI: 1.04–1.78) to report readmission to the ��������less Program of the VA Caribbean Healthcare System when compared to those who did not report social isolation [55].

Furthermore, people with severe mental health problems are generally at higher risk of being socially isolated or feeling alone. For example, Rodriguez-Moreno [31] compared homeless adult women at high risk of mental-ill health (HW-MI) and homeless women not at high risk of mental-ill health (HW-NMI) and found that HW-MI participants reported feeling significantly lonelier than homeless women without this risk (OR: 0.24, 95% CI 0.09–0.64).

Association between SIL, substance use, and social distress

None of the quantitative studies investigated the association between SIL and substance use, despite the fact that substance use is a prevalent issue among people with homelessness experience. However, some of the qualitative studies discussed how SIL and substance use are interconnected among people with experiences of homelessness [86]. Lafuente [36] reported participants relapsed to alcohol and other risk behaviors due to SIL: “I've started drinking and at this particular time. They offered to put me back into treatment and at this time I was not homeless…and I refuse it…the alcohol has really taken over me." Another study discussed how substance use contributed to SIL for participants who identified as male [59]. Participants discussed how the use of substances affected their social relationships in different ways including added strain, limited availability of resources from social relationships, and the interplay between substance use and feelings of social isolation at earlier and later stages in life [59].

Regarding social distress, Cruwys et al. [71] found that the social isolation schema predicted lower social identification with homelessness services. Individuals with negative experiences with homelessness services were less likely to become socially engaged with new groups, and this relationship remained over time. SIL was also associated with poor or restless sleeping patterns, particularly among women with restless sleep compared to men as reported by Davis et al. [85] Moreover, Tsai et al. [67] found that measures of loneliness (percentage relative importance = 17.12) as measured by the shortened revised version 3 of the UCLA Loneliness Scale and severity of substance use (percentage relative importance = 16.93) were the most important variables associated with any lifetime eviction and lifetime homelessness. Participants also depicted signs of social distress due to SIL, including fear of dying alone. Studies by Bazari et al. [87] and Finlay, Gaugler and Kane [88] highlighted the unique challenges of older adults with homelessness experience, including concerns of dying alone. Van Dongen et al. [89] examined medical and nursing records from 61 adults receiving end-of-life care in shelter-based nursing care settings in the Netherlands and found that one quarter (n = 15) of patients died alone.

Discussion

In this scoping review, we explored social isolation and loneliness (SIL) as an under-researched social determinant of health among individuals with experiences of homelessness or those who are marginally or vulnerably housed. We summarized findings from 52 studies published between 2000 and 2023. Our review detailed how these studies conceptualized SIL, including the scales and tools used for its measurement. We also reported on the prevalence of SIL and examined its associations with well-being, health and social outcomes, and substance use among people with experiences of homelessness.

Most studies included in this review were published in 2010 or later, which shows a growing interest in this area. However, studies that have a specific focus on SIL and associated health and social outcomes continue to be scarce. Only one-third of the studies included in this review identify SIL as their primary goal or one of their main research questions. Most of the quantitative studies used a cross-sectional methodology, and we did not find any intervention studies that addressed SIL among people with histories of homelessness as the primary or secondary outcome. Despite these limitations, the studies summarized in this review provide an important overview of SIL among people with histories of homelessness.

Three main theoretical corpuses were used to conceptualize SIL in the context of housing and homelessness experience across the studies: theory of social exclusion [36, 39, 58], theory of social disaffiliation [36], and theory of digital exclusion (also called digital divide) [90]. Some studies mentioned structural stigma and alienation to explain systematic biases, policies and practices resulting in reinforcing SIL among people with histories of homelessness, particularly among people who use alcohol and other substances [37]. This suggests that SIL is a complex issue, embedded in a larger societal problem of socio-economic exclusion, which makes people who are marginalized by structural systems feel invisible, powerless and detached from society. Moreover, the shift to a more digital world, which requires some digital literacy and access to��information and communication technologies, may lead to increased feelings of SIL and barriers to services for people with homelessness experience.

We found that the proportion of studied populations who reported SIL varies largely ranging from 25 to 90% across studies. However, the range of measurement scales used to measure SIL across studies limits consistency and comparability between studies. In addition, there are questions around the suitability and fitness of certain tools for measuring SIL among individuals who have experienced homelessness. For instance, the UCLA Loneliness Scale has been found to be challenging for Australians with cognitive disabilities [91], which is a common issue among some individuals experiencing homelessness [92]. Likewise, some tools focus on a single dimension [93] or use a single question [94], which limits their ability to capture the complex and multifaceted nature of SIL. A study conducted by Bower [75] identified several factors affecting the effectiveness and validity of SIL measures in marginalized groups while using the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA-S) with 128 homeless adults in Sydney, Australia. These factors included variations in loneliness dimensions (such as social, family, and romantic loneliness), the cognitive abilities of participants to understand and answer questions, and the necessity for cultural adaptation, as meanings can differ across countries and cultures.

Studies included in this review also showed how personal identities play a role in an individual’s perception of their experiences of SIL and how it affects them as they navigate health, social and housing services. In one study [33], a participant described how they were rejected from a shelter agency because they identified as transgender. This raises important questions about the inclusivity and equity of service provision and suggests that personal identity can significantly affect one's ability to access essential support. Other studies showed relationships between SIL, age and self-identifying as a woman. These findings are not only consistent with broader research [95, 96] but also underscore deeper, often systemic issues within social service frameworks [97]. The intersection of SIL with identity-related factors indicates that care and social services may be insufficiently trained and equipped to address the unique challenges faced by different demographic groups [98, 99].

Findings from studies included in this review show a relationship between SIL, health and social distress among people with homelessness experience. SIL was associated with poor sleeping patterns [85], and with lower social identification with homelessness services [71], with any lifetime eviction and lifetime homelessness [67]. Related to health, SIL is negatively associated with subjective health [66], self-reported illness [70], health and mental health among both men and women [74], severe mental health problems [31] and substance use [59]. These findings are in line with what has been reported in studies carried out in other population groups, where an association has been found between SIL and health behavior and physical heath [1, 100, 101] including risk of heart disease, stroke, hospitalization, death and mental health [3, 102, 103, 110, 111].

There are several potential reasons for the relationship between SIL, negative health [6] and desire to participate in social and physical activities [101, 104] or use healthcare services, thereby exacerbating pre-existing conditions or contributing to the emergence of new health problems [105, 106, 109]. For instance, some studies indicate that SIL can lead to reduced participation in social and physical activities, as well as lower utilization of social and healthcare services [43, 107]. This diminished engagement can subsequently heighten the likelihood of developing or worsening mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety [108].

Additionally, individuals with SIL combined with homelessness experience often suffer from a significant loss of self-esteem, self-worth, and self-confidence [36, 52].This situation can be worsened when individuals perceive that their SIL is related to ageism, racial or ethnic background or discrimination based on gender identity or sexual orientation [39]. The interplay of these factors can result in increased social withdrawal, decreased physical activity, and diminished engagement with healthcare services, all of which further elevate the risks for a range of physical and mental health problems [59, 103], including obesity and associated health issues, depression, food and sleeping issues, suicidal ideation and premature deaths [82,83,84].

Gaps in the existing literature and recommendations

We identified several gaps in the studies included in this review. First, SIL was not the primary objective of the majority of the included studies. Thus, there was limited interest to provide a clear definition of SIL or a detailed description of its measurement. Second, the quantitative studies used different measurement tools, with some of them not primarily conceived to measure SIL, thus making comparisons across studies difficult. Additionally, many of these studies used cross-sectional design and covered very small and not generally representative samples. Thus, the estimation of the prevalence of SIL among people with homelessness experience and living in supportive or social housing remained exploratory, and the studies cannot establish causality between SIL and physical or mental health conditions or with social wellbeing. Studies that are mainly focused on SIL, and more longitudinal and targeted interventions are required to better understand the potential links between SIL and these outcomes. Future studies must also include more specific and objective health outcomes like depression or anxiety disorder, drug and alcohol disorder, service use, suicidal ideation and attempts or premature aging, which are prevalent among people with homelessness experience [86]. Third, the existing literature is very limited in analyzing how SIL impacts some populations differently, in particular women [112, 113] and non-binary or gender-diverse groups [114, 115]. Mayock and Bretherton [116] discussed how gender shapes the trajectories of women experiencing homelessness. Research has demonstrated that women are often affected by and respond to homelessness in different ways than males, and thus have different experiences of homelessness [112]. Self-identified queer people/people who are sexually diverse and/or trans- and gender-diverse and are experiencing homelessness similarly have a distinct experience [114]. Hail-Jares et al. [115] discussed how queer youth experience higher rates of homelessness and greater housing instability compared to their cisgender and heterosexual counterparts. Gender diverse youth who must choose between staying in the family home, maintaining their LGBTQ2S identity, and continuing to be physically and mentally safe, often consider homelessness as the perceived safer option [117]. In addition, future homelessness-related studies examining SIL should seek to make methodological distinctions that reflect differences based on gender identity and not consider queer/gender-diverse people as a homogenous group.

Finally, we found no studies that specifically explored SIL among people with homelessness experience from a particular ethnicity. Given the significant impact of ethnicity on experiences of homelessness, it is likely that ethnicity plays an important role or has a multiplier effect in the way SIL is experienced [118, 119]. There is also a lack of geographic and regional representation across the studies, since most of them were conducted in the US and Canada. Further, research that includes diverse population and geographic regions would help inform broader policy change and programming for people from different cultural and ethnic groups.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, to ensure feasibility, the review exclusively included peer-reviewed articles published in English, French, and Spanish from the year 2000 onwards. This restriction could introduce publication bias and potentially omit relevant studies published in other languages or formats. Second, the review utilized a broad definition of both homelessness experience and health outcomes. This inclusive approach allowed the incorporation of a diverse range of studies from various countries and methodological approaches. However, this broad scope might have introduced heterogeneity that complicates the synthesis of findings. This lack of standardized definitions and measurements makes it challenging to compare and aggregate results across different studies.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our scoping review is the first in the literature to provide a deep and nuanced understanding of SIL that accounts for the theoretical conceptualizations, the measurement and complex interplay of identity and systemic barriers among people with homelessness experience. Our review points to the critical need for more research to better understand SIL among different populations experiencing marginalization and to assess the relationship between SIL and health and social outcomes. Testing and validating SIL measurement tools would help to improve the quality of evidence. Additional research with diverse populations and countries is urgently needed, along with interventional studies to build evidence to inform the development of actionable strategies to address SIL among people with homelessness experience. As implications for public policies, these studies highlight that SIL is a prevalent and significant issue in the lives of people with homelessness experience. There is a��lack of awareness and training of healthcare providers to recognize and understand SIL as a health risk factor in addition to other challenges for marginalized groups and in particular people with homeliness experience. It is crucial to develop and implement policies to create awareness and best practices that are sensitive to SIL as a growing public health issue and to advocate for systemic changes that address the root causes of discrimination and exclusion, in particular among people with homelessness experience or housing precarity.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in supplementary information files.

References

Holt-Lunstad J, Steptoe A. Social isolation: An underappreciated determinant of physical health. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;43:232–7. .

Benjaminsen L. The variation in family background amongst young homeless shelter users in Denmark. J Youth Stud. 19(1 PG-55–73):55–73.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. National Academies Press; 2020.

Courtin E, Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(3):799–812. .

Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness Matters: A Theoretical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(2):218–27. .

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and M. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults.; 2020.

Annuar AS, Rahman RA, Munir A, Murad A, El-enshasy HA, Illias R. Jo ur l P re. Carbohydr Polym. Published online 2021:118159.

Patterson ML, Currie L, Rezansoff S, Somers JM. Exiting homelessness: Perceived changes, barriers, and facilitators among formerly homeless adults with mental disorders. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(1):81–7. .

Bower M, Conroy E, Perz J. Australian homeless persons’ experiences of social connectedness, isolation and loneliness. Heal Soc Care Community. 2018;26(2):e241–8. .

Stergiopoulos V, Mejia-Lancheros C, Nisenbaum R, et al. Long-term effects of rent supplements and mental health support services on housing and health outcomes of homeless adults with mental illness: extension study of the At ��������/Chez Soi randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(11):915–25.

Mejia-Lancheros C, Lachaud J, Woodhall-Melnik J, O’Campo P, Hwang SW, Stergiopoulos V. Longitudinal interrelationships of mental health discrimination and stigma with housing and well-being outcomes in adults with mental illness and recent experience of homelessness. Soc Sci Med. 2021;268: 113463. .

O’Campo P, Stergiopoulos V, Davis O, et al. Health and social outcomes in the Housing First model: Testing the theory of change. eClinicalMedicine. 2022;47:101387.

Smith L, Veronese N, López-Sánchez GF, et al. Health behaviours and mental and physical health status in older adults with a history of homelessness: A cross-sectional population-based study in England. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):1–7. .

Hwang SW, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, O’Campo PJ, Dunn JR. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 Year follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339(7729):1068. .

Henwood BF, Byrne T, Scriber B. Examining mortality among formerly homeless adults enrolled in Housing First: An observational study. �������� Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–8. .

Brown RT, Guzman D, Kaplan LM, Ponath C, Lee CT, Kushel MB. Trajectories of functional impairment in homeless older adults: Results from the HOPE HOME study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):1–16. .

Wise B, Theis D, Bainter T, Sprinkle B. Going Forward as a Community: Assessment and Person-Centered Strategies for Reducing Impacts of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Nursing ��������s. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2023;31(3):S14. .

Howland J, Stone A. Public health nurses for case finding, assessment and referral of community-dwelling socially isolated and/or lonely older adults. Front Public Heal. 2023;11(5).

Holt-Lunstad J, Layton R, Barton B, Smith TB. Science into Practice: Effective Solutions for Social Isolation and Loneliness. Generations. 2020;44(3):1–10.

Mercer C. Primary care providers exploring value of “social prescriptions” for patients. CMAJ. 2018;190(49):E1463–4. .

Gibson K, Pollard TM, Moffatt S. Social prescribing and classed inequality: A journey of upward health mobility? Soc Sci Med. 2021;280(April): 114037. .

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. .

Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6. .

National Alliance to End ��������lessness. State of ��������lessness: 2021 Edition.; 2021.

Gaetz S, Dej E, Richter T, Redman M. The State of ��������lessness in Canada 2016.; 2016.

Marcal KE. A Theory of Mental Health and Optimal Service Delivery for ��������less Children. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2017;34(4):349–59. .

Searle C, van Vuuren JH. Modelling forced migration: A framework for conflict-induced forced migration modelling according to an agent-based approach. Comput Environ Urban Syst. 2021;85: 101568. .

Fante I, Daiute C. Applying qualitative youth and adult perspectives to investigate quantitative survey components with a novel “crosswalk” analysis. Methods Psychol. 2023;8: 100121. .

Vazquez JJ, Panadero S, Garcia-Perez C. Immigrant women living homeless in Madrid (Spain). Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2020;90(5):633–43.

Rodriguez-Moreno S, Panadero S, Vazquez JJ. Risk of mental ill-health among homeless women in Madrid (Spain). Arch Women Ment Heal. 2020;23(5):657–64. .

Davis JE, Shuler PA. A biobehavioral framework for examining altered sleep-wake patterns in homeless women. Issues Ment Heal Nurs. 2000;21(2):171–83.

Toolis E, Dutt A, Wren A, Jackson-Gordon R. “It’s a place to feel like part of the community”: Counterspace, inclusion, and empowerment in a drop-in center for homeless and marginalized women. Am J Community Psychol. 2022;70(1–2):102–16. .

Ebied EMES, Eldardery NES. Lived experiences of homelessness among elderly women: A phenomenological study. Pakistan J Med Heal Sci. 2021;15(8):2413–2420.

Archard P, Murphy D. A practice research study concerning homeless service user involvement with a programme of social support work delivered in a specialized psychological trauma service. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015;22(6):360–70. .

Lafuente CR. Powerlessness and social disaffiliation in homeless men. J Multicult Nurs Heal. 2003;9(1):46–54.

Bell M, Walsh CA. Finding a Place to Belong: The Role of Social Inclusion in the Lives of ��������less Men. Qual Rep. 2015;20(12):1977–1994. http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fscholarly-journals%2Ffinding-place-belong-role-social-inclusion-lives%2Fdocview%2F1753369890%2Fse-2https://librarysearch.library.utoronto.ca/openurl/01UTORONTO_INST/01UTORONTO.

Lehmann RJB, Hausam J, Losel F. Stigmatization and Victimization of People Experiencing ��������lessness: Psychological Functioning, Social Functioning, and Social Distance as Predictors of Reporting Violence to the Police(1). Polic-J Policy Pr.:15.

Burns VF, Leduc JD, St-Denis N, Walsh CA. Finding home after homelessness: older men’s experiences in single-site permanent supportive housing. Hous Stud. 2020;35(2):290–309. .

Patanwala M, Tieu L, Ponath C, Guzman D, Ritchie CS, Kushel M. Physical, Psychological, Social, and Existential Symptoms in Older ��������less-Experienced Adults: An Observational Study of the Hope �������� Cohort. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):635–43. .

Grenier A, Sussman T, Barken R, Bourgeois-Guerin V, Rothwell D. “Growing Old” in Shelters and “On the Street”: Experiences of Older ��������less People. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2016;59(6):458–477. https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med13&AN=27653853http://resolver.ebscohost.com/openurl?sid=OVID:medline&id=pmid:27653853&id=10.1080%2F01634372.2016.1235067&issn=0163-4372&isbn=&volume=59&issue=6&spage=458&date=201.

Kirst M, Zerger S, Wise Harris D, Plenert E, Stergiopoulos V. The promise of recovery: narratives of hope among homeless individuals with mental illness participating in a Housing First randomised controlled trial in Toronto, Canada. BMJ Open. 4(3 PG-e004379):e004379.

Bower M, Conroy E, Perz J. Australian homeless persons’ experiences of social connectedness, isolation and loneliness. Health Soc Care Community. 26(2 PG-241–248):e241-e248.

Noble A, Owens B, Thulien N, Suleiman A. “I feel like I’m in a revolving door, and COVID has made it spin a lot faster”: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth experiencing homelessness in Toronto, Canada. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(8): e0273502. .

Mejia‐Lancheros C, Alfayumi‐Zeadna S, Lachaud J, et al. Differential impacts of <scp>COVID</scp> ‐19 and associated responses on the health, social well‐being and food security of users of supportive social and health programs during the <scp>COVID</scp> ‐19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(6).

Rew L. Friends and Pets as Companions: Strategies for Coping With Loneliness Among ��������less Youth. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2000;13(3):125–32. .

Rokach A. The Loneliness of Youth ��������less. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2006;13(1–2):113–26. .

Rokach A. ��������less Youth: Coping with Loneliness. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2005;12(1–2):91–105. .

Rokach A. The causes of loneliness in homeless youth. J Psychol. 2005;139(5):469–480. https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med6&AN=16285216http://resolver.ebscohost.com/openurl?sid=OVID:medline&id=pmid:16285216&id=10.3200%2FJRLP.139.5.469-480&issn=0022-3980&isbn=&volume=139&issue=5&spage=469&date=2005&t.

Rew L. Friends and pets as companions: strategies for coping with loneliness among homeless youth. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2000;13(3):125–132. https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med4&AN=11111505http://resolver.ebscohost.com/openurl?sid=OVID:medline&id=pmid:11111505&id=10.1111%2Fj.1744-6171.2000.tb00089.x&issn=1073-6077&isbn=&volume=13&issue=3&spage=125&date.

Noble A, Owens B, Thulien N, Suleiman A. “I feel like I’m in a revolving door, and COVID has made it spin a lot faster”: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth experiencing homelessness in Toronto, Canada. PLoS ONE Vol 17(8), 2022, ArtID e0273502. 2022;17(8).

Johari F, Iranpour A, Dehghan M, Alizadeh S, Safizadeh M, Sharifi H. Lonely, harassed and abandoned in society: the lived experiences of Iranian homeless youth. �������� Psychol. 2022;10(1):75. .

Winer M, Dunlap S, Pierre CS, McInnes DK, Schutt R. Housing and Social Connection: Older Formerly ��������less Veterans Living in Subsidized Housing and Receiving Supportive Services. Clin Gerontol. 2021;44(4):460–9. .

Novacek DM, Wynn JK, McCleery A, et al. Racial differences in the psychosocial response to the COVID-19 pandemic in veterans with psychosis or recent homelessness. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2022;92(5):590–8. .

Rivera-Rivera N, Villarreal AA. ��������less veterans in the Caribbean: Profile and housing failure. Rev Puertorriquena Psicol. 2021;32(1):64–73. https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=pmnm&AN=35765409http://resolver.ebscohost.com/openurl?sid=OVID:medline&id=pmid:35765409&id=doi:&issn=1946-2026&isbn=&volume=32&issue=1&spage=64&date=2021&title=Revista+Puertorriquena+de.

Bige N, Hejblum G, Baudel JL, et al. ��������less Patients in the ICU: An Observational Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(6):1246–54. .

Muir K, Fisher KR, Dadich A, Abello D. Challenging the exclusion of people with mental illness: the Mental Health Housing and Accommodation Support Initiative (HASI). Aust J Soc Issues. 2008;43(2):271–90. .

Baker S, Warburton J, Hodgkin S, Pascal J. The supportive network: rural disadvantaged older people and ICT. Ageing Soc. 2017;37(6):1291–309. .

Jurewicz A, Padgett DK, Ran Z, et al. Social relationships, homelessness, and substance use among emergency department patients. Subst Abus. 2022;43(1):573–80. .

Martinez AA, Pacheco MP, Martinez MA, Alcibar NA, Astondoa EE. Understanding Loneliness and Social Exclusion in Residential Centers for Social Inclusion. Soc Work Res. 2022;46(3):242–254.

Johnstone M, Jetten J, Dingle GA, Parsell C, Walter ZC. Enhancing well-being of homeless individuals by building group memberships. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2016;26(5):421–38. .

Polvere L, Macnaughton E, Piat M. Participant perspectives on housing first and recovery: early findings from the At ��������/Chez Soi project. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2013;36(2):110–2. .

Rokach A. Private lives in public places: Loneliness of the homeless. Soc Indic Res. 2005;72(1):99–114. .

Rokach A. The Lonely and ��������less: Causes and Consequences. Soc Indic Res. 2004;69(1):37–50. .

Bilsky, Wolfgang; Hosser D. Social Support and Loneliness: Psychometric Comparison of Two Scales Based on a Nationwide Representative Survey.

Drum JL, Medvene LJ. The social convoys of affordable senior housing residents: Fellow residents and “Time Left.” Educ Gerontol. 2017;43(11):540–51. .

Tsai J, Grace A, Vazquez M. Experiences with Eviction, House Foreclosure, and ��������lessness Among COVID-19 Infected Adults and Their Relation to Mental Health in a Large U.S. City. J Community Heal. 2022;11:11.

Dost K, Heinrich F, Graf W, et al. Predictors of Loneliness among ��������less Individuals in Germany during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Heal. 2022;19(19):11. .

Ferrari JR, Drexler T, Skarr J. Finding a spiritual home: A pilot study on the effects of a spirituality retreat and loneliness among urban homeless adults. Psychology. 2015;6(3):210–6. .

Valerio-Urena G, Herrera-Murillo D, Rodriguez-Martinez MD. Association between perceived loneliness and Internet use among homeless people. Saude E Soc. 2020;29(2).

Cruwys T, Dingle GA, Hornsey MJ, Jetten J, Oei TP, Walter ZC. Social isolation schema responds to positive social experiences: longitudinal evidence from vulnerable populations. Br J Clin Psychol. 2014;53(3):265–80. .

Wrucke B, Bauer L, Bernstein R. Factors Associated with Cigarette Smoking in ��������less Adults: Findings From an Outpatient Counseling Clinic. Wis Med J. 2022;121(2):106–110. https://wmjonline.org/past-issues/https://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emexb&AN=2017708855https://librarysearch.library.utoronto.ca/openurl/01UTORONTO_INST/01UTORONTO_INST:UTOR.

Campo Ferreiro I, Haro Abad JM, Rigol Cuadra MA. Loneliness in homeless participants of a housing first program outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2021;59(3):44–51. .

Pedersen P V, Gronbaek M, Curtis T. Associations between deprived life circumstances, wellbeing and self-rated health in a socially marginalized population. Eur J Public Heal. 2012;22(5):647–652. https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med9&AN=21920848http://resolver.ebscohost.com/openurl?sid=OVID:medline&id=pmid:21920848&id=10.1093%2Feurpub%2Fckr128&issn=1101-1262&isbn=&volume=22&issue=5&spage=647&date=2012&title.

Bower M, Gournay K, Perz J, Conroy E. Do we all experience loneliness the same way? Lessons from a pilot study measuring loneliness among people with lived experience of homelessness. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(5).

Kaplan LM, Sudore RL, Arellano Cuervo I, Bainto D, Olsen P, Kushel M. Barriers and Solutions to Advance Care Planning among ��������less-Experienced Older Adults. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(10):1300–6. .

Pedersen PV, Andersen PT, Curtis T. Social relations and experiences of social isolation among socially marginalized people. J Soc Pers Relat. 2012;29(6):839–58. .

Kirst M, Zerger S, Harris DW, Plenert E, Stergiopoulos V. The promise of recovery: Narratives of hope among homeless individuals with mental illness participating in a Housing First randomised controlled trial in Toronto, Canada. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3) (no pagination). https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed15&AN=372764346https://librarysearch.library.utoronto.ca/openurl/01UTORONTO_INST/01UTORONTO_INST:UTORONTO?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&rfr_id=info:si.

Mejiaâ€-Lancheros C, Alfayumiâ€-Zeadna S, Lachaud J, et al. Differential impacts of COVIDâ€-19 and associated responses on the health, social wellâ€-being and food security of users of supportive social and health programs during the COVIDâ€-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(6):e4332-e4344.

Piat M, Sabetti J, Padgett D. Supported housing for adults with psychiatric disabilities: How tenants confront the problem of loneliness. Heal Soc Care Community. 2018;26(2):191–8. .

Henwood BF, Lahey J, Harris T, Rhoades H, Wenzel SL. Understanding Risk Environments in Permanent Supportive Housing for Formerly ��������less Adults. Qual Heal Res. 2018;28(13):2011–9. .

Pilla D, Park-Taylor J. “Halfway Independent”: Experiences of formerly homeless adults living in permanent supportive housing. J Community Psychol.

Parkes T, Carver H, Masterton W, et al. “You know, we can change the services to suit the circumstances of what is happening in the world”: a rapid case study of the COVID-19 response across city centre homelessness and health services in Edinburgh, Scotland. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1):64. .

Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum. 1989;1:139–67.

Davis JE, Shuler PA. A biobehavioral framework for examining altered sleep-wake patterns in homeless women. Issues Ment Heal Nurs. 2000;21(2):171–183. https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med4&AN=10839059http://resolver.ebscohost.com/openurl?sid=OVID:medline&id=pmid:10839059&id=10.1080%2F016128400248176&issn=0161-2840&isbn=&volume=21&issue=2&spage=171&date=2000&title.

Barry R, Anderson J, Tran L, et al. Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders Among Individuals Experiencing ��������lessness. JAMA Psychiat. 2024;81(7):691. .

Bazari A, Patanwala M, Kaplan LM, Auerswald CL, Kushel MB. “The Thing that Really Gets Me Is the Future”: Symptomatology in Older ��������less Adults in the HOPE HOME Study. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;56(2):195–204. .

Finlay JM, Gaugler JE, Kane RL. Ageing in the margins: Expectations of and struggles for “a good place to grow old” among low-income older Minnesotans. Ageing Soc. 2020;40(4):759–83. .

van Dongen SI, Klop HT, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. End-of-life care for homeless people in shelter-based nursing care settings: A retrospective record study. Palliat Med. 2020;34(10):1374–84. .

Scott H, Bryant T, Aquanno S. The Role of Transportation in Sustaining and Reintegrating Formerly ��������less Clients. J Poverty. 2020;24(7):591–609. .

Stancliffe RJ, Wilson NJ, Bigby C, Balandin S, Craig D. Responsiveness to self-report questions about loneliness: a comparison of mainstream and intellectual disability-specific instruments. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2014;58(5):399–405. .

Buhrich N, Hodder T, Teesson M. Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment Among ��������less People in Inner Sydney. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(4):520–1. .

De Jong GJ, Van Tilburg T. The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur J Ageing. 2010;7(2):121–30. .

Pedersen ER, Tucker JS, Kovalchik SA. Facilitators and Barriers of Drop-In Center Use Among ��������less Youth. J Adolesc Heal. 2016;59(2):144–53. .

Röhr S, Wittmann F, Engel C, et al. Social factors and the prevalence of social isolation in a population-based adult cohort. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(10):1959–68. .

Umberson D, Lin Z, Cha H. Gender and Social Isolation across the Life Course. J Health Soc Behav. 2022;63(3):319–35. .

Santos P, Faughnan K, Prost C, Tschampl CA. Systemic barriers to care coordination for marginalized and vulnerable populations. J Soc Distress ��������lessness. 2023;32(2):234–47. .

Matsuzaka S, Hudson KD, Ross AM. Operationalizing Intersectionality in Social Work Research: Approaches and Limitations. Soc Work Res. 2021;45(3):155–68. .

Budge SL, Adelson JL, Howard KAS. Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(3):545–57. .

Schrempft S, Jackowska M, Hamer M, Steptoe A. Associations between social isolation, loneliness, and objective physical activity in older men and women. �������� Public Health. 2019;19(1):74. .